Born on October 27, 1942, Fred ‘Zab’ Zabitosky grew up with little discipline. Vandalism and petty theft had earned him some time in the reformatory in Trenton, New Jersey, while an unhappy home life had him running away frequently. Trouble was something with which he was intimately familiar.

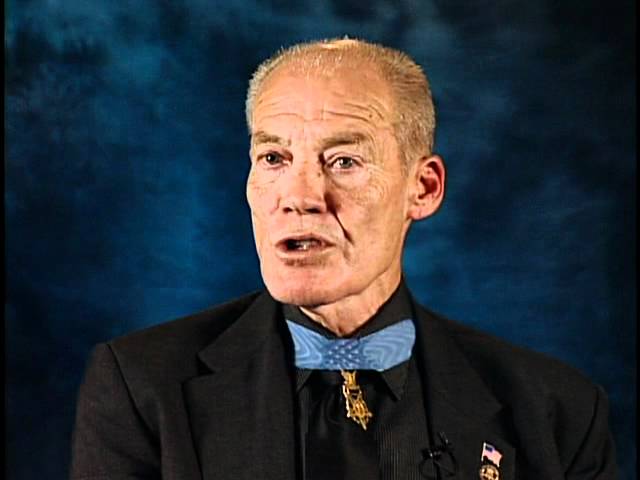

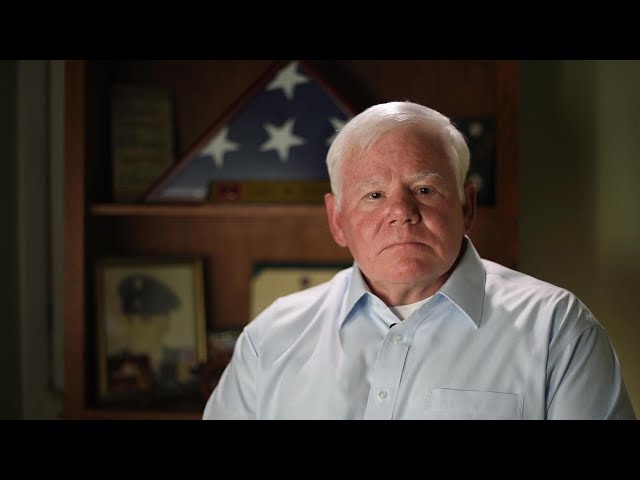

When he joined the Army at the age of 17, Zabitosky found the home he had never had. ‘I loved the discipline and I loved the pride,’ remembers Zabitosky. ‘This was the first time I ever experienced either.’

Basic training was also the first time he had ever been out of the New Jersey area. He trained in Fort Benning, Ga., and did well. By the time he returned to Vietnam for his third tour in September 1967, he was a combat-ready Green Beret who knew his job.

Zabitosky was assigned to Military Assistance Command Vietnam’s Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG), Operations Project 35, also known as ‘Shining Brass’ and code-named ‘Prairie Fire.’ Its mission was to conduct secret operations into Laos and Cambodia. The operation, conducted from Kontum at Forward Operational Base No. 2, had been going on for two years; Zabitosky’s mission was to infiltrate across the Laotian and Cambodian borders to monitor the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

Zabitosky was made the leader of Spike Team Maine, which consisted of three Americans and nine indigenous troops, usually Chinese Nungs. Because his team was operating in unconventional warfare mode, the men wore no uniforms. In fact, they wore either North Vietnamese clothes or generic military fatigues without any identification. Their rifles were either Russian AK-47s or Swedish K-submachine guns. They carried North Vietnamese combat gear and ate only Vietnamese food. Before a mission, they didn’t wash for several days, since they didn’t want to smell like Americans.

For Staff Sgt. Doug Glover, the MACV-SOG missions were his first combat assignments. By the time Glover was ready for his third mission on February 18, 1968, he was made a team leader and he and Zabitosky were friends. The Tet Offensive had begun, and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops were using Laos and Cambodia as their staging areas. A decision was made to infiltrate five MACV-SOG teams into Cambodia and Laos to determine enemy troop concentrations and to decide if a second enemy offensive was probable.

The night before the mission, Glover told Zabitosky: ‘I had a dream that I’m going to get killed. I know I’m going to die tomorrow.’ On hearing that, Zabitosky realized that his friend was not confident enough to lead a team the next day, and he responded, ‘Doug, I’ll go in with you as your assistant team leader.’

The next day, two helicopters carrying the team landed east of Attopeu, Laos. As the Green Berets moved through 10-foot-tall elephant grass and bamboo thickets near the landing zone (LZ), Zabitosky could see that Glover was uncomfortable.

The team members started into the jungle and suddenly realized they were in the middle of an NVA complex. There were bunkers and K-wire everywhere. But the real tip-off was the enemy soldiers sitting at their campsites, eating. Just as the Green Berets realized where they were, the NVA realized it, too. All of a sudden, guns started blazing from both sides. The team dropped back.

Zabitosky asked Glover what he wanted to do. ‘You take over the team,’ Glover responded. ‘You got to take over the team.’ Zabitosky said, ‘All right, move the men back to the LZ, and I’ll stay here and cover.’ The team withdrew. ‘I wanted them out of there. I had my hands full and I work better alone,’ remembers Zabitosky. ‘The team had a better chance of survival at the LZ.’

Zabitosky started to withdraw, firing his M-16 as he moved back and setting Claymore mines connected to white phosphorus ‘Willy-Peter’ grenades. He radioed Glover to call in airstrikes on the white smoke as soon as the grenades started going off. A Douglas Skyraider A1-E strike force was on the way.

When the phosphorus grenades started to blow, the bombers dropped in. Zabitosky had no way to communicate directly with the aircraft himself, and now 750-pound bombs and napalm were dropping all around him. Dozens of NVA were still making their way toward him. ‘I finally made it back to the LZ with the rest of the squad, but there were no helicopters to get us out of there yet,’ he recalls. Realizing they would have to buy time, he positioned each man around a tight perimeter defense just outside the LZ.

Glover was the radioman now. The FAC (forward air control) plane, flying above the surrounded troops, asked if there were any more Americans outside the defended area. When the pilot was told no, he called the A1-Es even closer, creating a scorching ring of fire. Napalm, 750-pound bombs and cluster bomb units (CBUs) were dropped on the surrounded Green Berets’ perimeter. The NVA kept attacking with wave after wave of frontal assaults. Over the next 11Ž2 hours, the overhead FAC aircraft counted 22 separate attacks made by four NVA companies. Zabitosky’s team was running out of ammo.

Finally, some Bell UH-1’slicks’ arrived. These unarmed, stripped bare utility helicopters were designed to carry as many troops as possible. Two of the choppers came over the team, while a third circled above them. Medic Luke Nance was in the third helicopter.

The slicks informed the team that they couldn’t bring their ships down on their LZ–it was too ‘hot.’ The team was ordered to a new LZ about 500 meters away. The NVA continued attacking. ‘We had been in battles this intense before, but none so prolonged,’ explains Zabitosky. ‘I was still in charge, and I was standing and trying to direct our fire and movement to the new LZ. When you are in charge, your men look to you for guidance, and you don’t want them to know you are as scared as they are.’ He knew their time was running out along with their ammunition and luck.

The team started moving toward the second LZ. The American air attackers increased their barrage on the surrounding enemy, which allowed Zabitosky and his men to reach the clearing just as the first slick landed. Zabitosky ordered two Nungs and one American onto the helicopter.

The NVA realized what the Americans were doing just as the first helicopter took off and the second landed. The enemy troops regrouped and started moving toward the new position. Zabitosky’s team kept firing. It looked as if they were going to make it out, even though it would be close.

Glover looked at Zabitosky, smiled, and said, ‘You brought us through again, Zab.’ Zabitosky replied, ‘You see, you had nothing to worry about with that dream.’

The six remaining team members ran to the open door of the second helicopter. Zabitosky ran to the left side, firing at the onrushing NVA while the other men got in on the right. The NVA were getting closer, and Zabitosky hung out the door, spraying automatic fire as the helicopter took off. The helicopter’s machine-gunners were firing, too, but suddenly the ship’s tail boom was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade.

‘There was a violent jolt, followed by screaming,’ Zabitosky remembers. ‘I saw the tail boom come around and I heard an explosion. Then I remember falling. It was like a dream.’ The helicopter crashed and Zabitosky landed about 20 feet from the burning wreckage. He was on fire, and he remembers thinking that he was near a very hot sun. When he started coming to, he realized the ‘hot sun’ was the blazing helicopter, and he was in the fight of his life. His clothes were in flames, and he could hear screams coming from the downed chopper. He knew he was hurt, and his first thought was, ‘Don’t let them catch you or they’ll kill you.’ He wanted to crawl into the bush and maybe be rescued. But he heard the screams from the helicopter again.

The ship’s fuel cells and ordnance were going off, and Zabitosky knew five of his team members were still in the bird, along with two pilots and two machine-gunners. He was the only one who had been thrown clear of the helicopter, which had broken at midsection and twisted on its right side. ‘I was out of ammunition, and the barrel of my rifle was bent from the fall,’ he remembers. ‘Now, all of a sudden, I was faced with the possibility of losing my whole team. I was hurting bad.’

Zabitosky had broken his back and several ribs in the crash. Despite his injuries, he managed to fight his way to the cockpit and started dragging out a dazed pilot.

He remembers, ‘I dragged the pilot out and saw he was awake. I asked him to help me get the co-pilot, who was still screaming. The pilot refused, saying it was too late and there was no chance the co-pilot could live. He left me, dragging my bent gun with him.’

Green Beret medic Luke Nance, who was in one of the rescue helicopters, remembers: ‘We were receiving fire and I saw Zab’s helicopter go down. It was exploding, but I thought I saw something move just outside.’ The pilots in the helicopter overhead were convinced that no one survived the crash, and they started to leave the area. Nance went to the cockpit and calmly said: ‘No, we’re not leaving. We’re going down there.’ Looking into his face, the pilots realized the Green Beret meant what he said. They were on their way down to the crash site.

Nance’s helicopter came down about 60 meters from the crashed helicopter, and the injured pilot Zabitosky had rescued earlier started crawling toward them.

‘We went down but didn’t quite land,’ Nance remembers. ‘I jumped out of the chopper and shot an NVA point-blank out of a tree. There was a lot of fire, and there were NVA troops coming at us. I could see men still alive, and I wanted to get to them.’

Despite the continued NVA attack, Zabitosky started into the burning helicopter again. The co-pilot kept yelling: ‘Help me! Please, help me!’

‘I made my way inside the cockpit and was able to get to his side,’ Zabitosky recalls. ‘I felt my face and shirt burning.’ The last fuel cell blew as he started dragging the co-pilot out. ‘We were thrown clear, but both of us were on fire. I started dragging him toward the chase copter. He only had a leather pistol belt left on. Everything else was burned off.’

Zabitosky remembers the co-pilot saying to him: ‘Thanks for not leaving me. Are we going to make it?’ Zabitosky replied, ‘I really don’t think so, but we’ll try.’

The only weapons he had left were a pistol and one hand grenade. The NVA had been held outside the LZ perimeter by the intense air support, but now some enemy soldiers were starting to get through. ‘I pulled the pin on my hand grenade and was ready to just let it blow,’ recalls Zabitosky, ‘but at the last second I threw it toward some attacking soldiers.’

Zabitosky hoisted the co-pilot on his shoulder and painfully made his way toward the chase helicopter. On the way, he saw the pilot, who was still on his hands and knees. ‘I considered leaving him, but I didn’t; I started dragging him, too,’ he recalls. ‘We got within 10 feet of the rescue ship and I remember Luke Nance’s skinny little hands coming to our rescue. He saved my life.’ Evacuated to Pleiku, Zabitosky would be hospitalized for six weeks.

Several hundred enemy soldiers were killed that day, including 109 at the first LZ. The crashed helicopter’s two machine-gunners, Spc. 4 Melvin C. Dye and Spc. 4 Robert S. Griffith, and three Nungs died in the crash. The co-pilot died two days later. Glover also died in the crash; sadly, his dream came true.

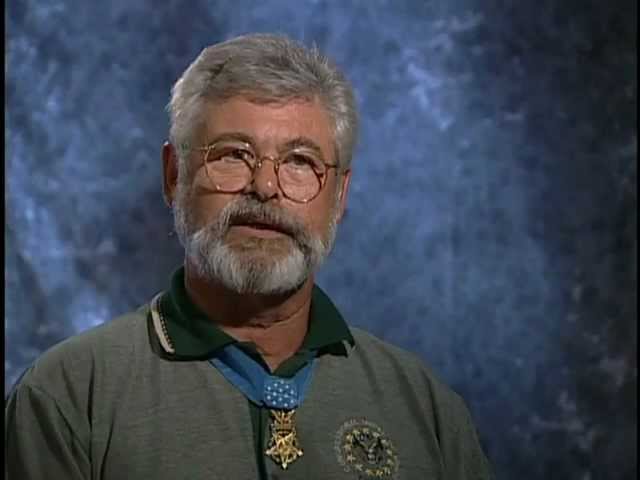

‘There is no such thing as patriotism in a combat situation,’ says Zabitosky, looking back at the mission. ‘You don’t think about medals, promotions or even the flag. You don’t think about why you are there or even your family. You think strictly about the people you are with, and what you can do for each other.’

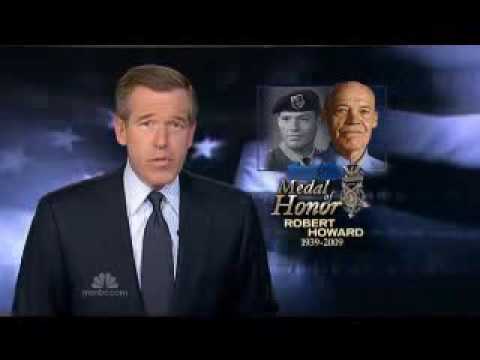

President Richard M. Nixon presented the Medal of Honor to Fred Zabitosky in March 1969 for his heroic efforts during the classified 1967 mission. ‘I wear the medal, but it was earned by Doug Glover, my indigenous team members and all the Special Forces enlisted men who served on special projects,’ says Zabitosky. ‘All the guys who wore that beret in combat have done just as much as I have, even though they may not have received the Medal of Honor.’

— Written by Dr. Kent DeLong and originally published in the February 1996 issue of Vietnam Magazine.